Native women extractivists and farmers in the Amazon work with a diverse array of products. They harvest chestnuts, babassu, extract oils, produce cassava flour, fruit pulp, plant cocoa, pepper, produce handicrafts and cultivate many other types of food in their backyards, their fields and their forests.

They use techniques of “farming without fire”, a production method that is very common in the Amazon and that does not require fire to “clear” the land. It requires fertilizing with crop and forest waste, which helps conserve the soil and the biodiversity. They grow their products in Agroforestry Systems (Sistemas Agroflorestais – SAFs), which is another technique that uses a diversity of species and that provides food, income and preserves natural resources, without the use of chemicals.

Production is in itself a daily struggle, but it is not the only struggle these women, who live and work in the Amazon, must face. The women extractivists and farmers of the Amazon want to defend their territories. It may be a collective territory like the Paraíso Sustainable Development Project in the municipality of Alenquer, or small private areas purchased or inherited from their families as in São Félix do Xingu, both municipalities in Pará state where many economic interests overlap, and the authorities often cannot get there in time to resolve problems or enforce the law. In these conditions, groups of family farmers, extractivists and particularly women struggle in their communities to uphold their rights, their land and their way of life.

The difficulties of this daily struggle are felt hardest by the women, who need to reconcile the tasks of production and social reproduction, in other words, the domestic chores of home and children, with agricultural and extractive production while defending their territories. As such, these women want information, and technological tools may be the solution they are looking for.

Territories such as Paraíso SDP, for example, given its size, can only be mapped and understood in its entirety by using tools that can record images, locate rivers, roads, production areas and the real threats to which they are subjected.

The women of Paraíso SDP are not able to know the exact size of their crop areas, as well as the environmental and conservation conditions of these areas, and an app using geospatial information could help them estimate the productive potential of different resources within the territory. They also would like to get information on family farming within the territory, how many families live there, what they produce and where they are located. With this information in hand, they would be in a better position to plan the territory’s development as well as to defend it.

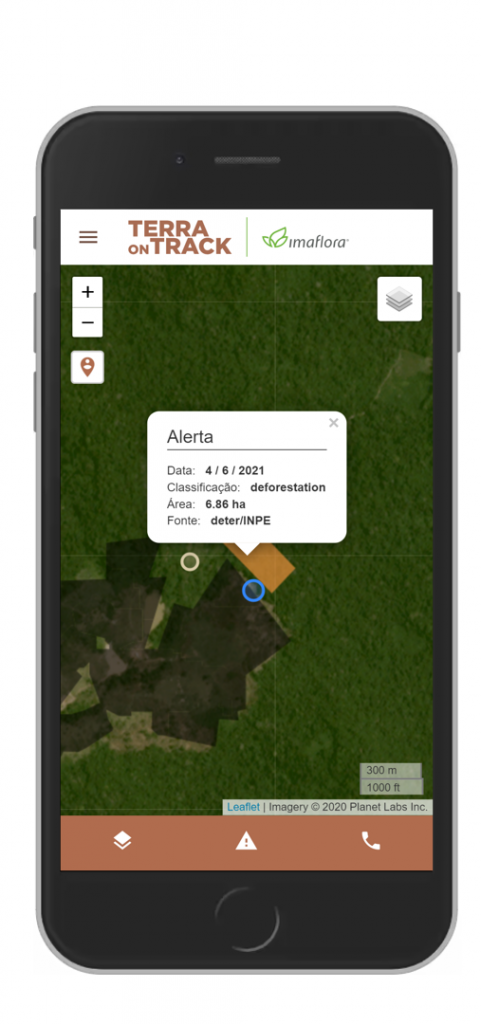

As such, a geospatial tool, such as the TerraOnTrack app, has enabled these women to see how accessing this information can help them. They have understood that the app is a two-way tool. On the one hand, they can add information to a platform that gathers qualified data for research and land management, and on the other, they can access the platform and see their territory in a broad and qualified way, using the app as a tool for planning and defense.

As such, a geospatial tool, such as the TerraOnTrack app, has enabled these women to see how accessing this information can help them. They have understood that the app is a two-way tool. On the one hand, they can add information to a platform that gathers qualified data for research and land management, and on the other, they can access the platform and see their territory in a broad and qualified way, using the app as a tool for planning and defense.

But their dreams don’t stop there. As a result of the needs of the communities where they live, they have suggested other functionalities for the app, such as the mapping of endemic diseases, public education and health facilities, natural resources for tourism, among other resources that, once mapped, can be used, managed, cared for and protected.

For the women farmers of the Association of Women Fruit Pulp Producers (Associação das Mulheres produtoras de Polpa de Frutas – AMPPF) in São Félix do Xingu, other issues are part of their daily struggle.

They live on small plots of land where they grow their agricultural produce within agroforestry systems. Many fruit trees have been introduced in these orchards, which already had existing fruit trees, enabling the production of fruit pulp. They have organized themselves into an association through which they acquire equipment for pulp production and have joined a public procurement project to sell the pulp to the municipality’s school meal program.

Everything would be going well were it not for the threats that some of these women farmers suffer as a result of the spraying of chemical products carried out by the large neighboring cattle farms. This chemical, which drifts into their plantations, kills the cocoa and other fruit crops in their orchards. In addition, illegal mining pollutes the rivers, affecting fishing and leisure activities in the communities of São Félix do Xingu.

The women have seen the potential of a geospatial tool in the defense of territory and have suggested that an app of this nature could be used to identify the centers of agrochemical use because they perceive this practice as a threat, not only to their crops but to the territory as a whole.

In short, how can a GIS tool potentially help these native women extractivists and smallholder farmers in the Amazon? In their view, a tool that collects information about the municipality, which shows the spatial dimensions where they are located helps them understand the context where they live. They believe in the importance of gathering real information on what happens on the land and about the threat to the natural and productive resources of their communities and believe they can help to map these extensive territories in the Amazon. In their eyes, an app that adds information to a system is useful to the extent that the information can be used by official authorities and organizations to better understand the problems and needs of these communities so that public policies can be created, and projects and solutions can be developed for the problems they face on a daily basis.